Janisha Chatterjee is a woman tangled up in layered identities. She lives during the heyday of British imperial rule, which is powered by mysterious technology known as Annapurnite. The privileged daughter of an Indian government official, Jani is an accomplished citizen of Empire—modern, secular, and studying medicine at Cambridge. She feels increasingly at odds, however, with the world around her: not fully fitting in as a mixed-race woman on the streets of London or in the market squares of Delhi. She also has growing reservations about the Raj, despite her father’s accomplishments as Minister of Security.

When her father falls gravely ill, she takes the first dirigible back east. The Rudyard Kipling’s journey, unfortunately, is cut short by a Russian attack that kills nearly everyone on board. One of the few survivors amongst the wreckage, Jani discovers that the airship had been transporting a most unusual prisoner. This stranger bestows a dangerous gift to Jani that reveals the British Empire’s source of military might…. and a dire warning about a threat which endangers the entire world.

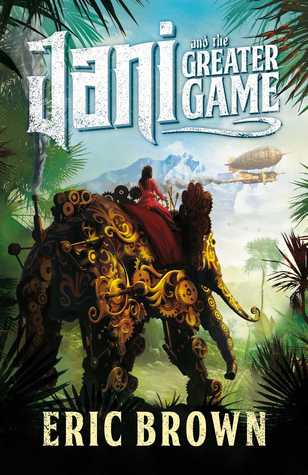

Russian spies, sadistic British officers (and even more sadistic assassins), religious zealots, and a giant clockwork-and-steam-powered elephant all make Jani and the Greater Game by Eric Brown a fast-paced romp through territory steampunk novels typically do not navigate. While this pulp-inspired adventure is a fun, though flawed, read, it gives the genre a much-needed breath of fresh air in many ways.

The book is set mostly in India, and Brown does a worthy job portraying the various parts of the country that Jani travels through. Additionally, he presents a clear historical understanding of the Angl0-Indian cultural fusion that was life under the Raj. I especially liked the natural and distinctive dialogue that he creates between his British, Anglo-Indian, and Indian characters.

The greatest strength behind Jani and the Greater Game is Brown’s ability to balance a sense of galloping fun while also injecting the story with harder-edged questions about British imperialism, racial identity, and class dynamics. Many sides to the Raj are seen: from Kapil Dev Chatterjee’s rose-tinted view of the British as the best of all possible European conquerors to Durga Das’s fervent animosity toward the British in his service to Kali (one nitpick here: Durga is a female name, and while Kali is the destructive manifestation of this goddess, it threw me that a male character would share her moniker).

The Brits are similarly divided, as the embittered Colonel Smethers unflinchingly suppresses the “brown savages” while sympathetic Lt. Alfred Littlebody would rather flee than shoot at a crowd of protestors. Jani herself is torn between her dual loyalties, which remains an unsolved struggle by the close of the book.

Colorful characters leap from the pages, larger-than-life: the feisty matron Lady Eddington and her Pullman car which she even takes aboard airships so she can travel in style; the loyal and clever Anand Doshi, a houseboy turned tinker’s apprentice who carries a flame for Jani; the effusive Brahmin Mr. Clockwork and his amazing inventions; the frightening pair of Russian spies that made me flinch every time they made an appearance on the page. Not to mention Jelch, the stranger who is from a realm far beyond anyone’s imaginations.

A major weak point of the novel, however, is that it is one long chase scene, typically with Jani repeatedly being captured by one faction or another and somehow managing to escape—usually by being rescued by a male character. Jani herself is smart, practical, and manages to put in a good fight or two when cornered, but the end result is always her getting drugged or gassed or knocked unconscious—and even one attempt to toss her into a trunk. While I would not classify her as a helpless damsel-in-distress, she is constantly put in situations for much of the book where, inevitably, her only chance of escape is through the power of another. Only in the final third of the book, when Jelch and his secrets are all revealed, is Jani given the opportunity to do something that only she can do.

That fault aside, much of the book switches POVs between parties—Russian, British, and Indian alike—all trying to put tabs on the fleeing Jani (who is assisted by young Anand), making the book incidentally feeling less like a Greater Game and more like an round of, “Where in the World is Janisha Chatterjee?” Several scenes remain compellingly intense, however, in particular a game of Russian Roulette between Smethers and Littlebody.

The book ends as Jani travels to London on the next leg of her quest to protect the world, with her friend Anand and their unexpected ally Littlebody in company. While I didn’t love the reactionary role Jani played in this novel, I am interested enough in following her back to England and hope she is finally given the chance to truly shine on her own.

Jani and the Greater Game is available now from Solaris.

Ay-leen the Peacemaker (or in other speculative lights, Diana M. Pho) works at Tor Books, runs the multicultural steampunk blog Beyond Victoriana, pens academic things, and tweets. Oh wait, she has a tumblr too.